How can we create a house that holistically advances architecture through agendas of on-site assembly, design for disassembly, and reuse of materials?

The project was named to evoke a familiar material and capture the essence of a sheer plastic, thinly wrapped residence.

© Peter Aaron/OTTO

In 2008, 500 architects were asked to submit proposals for full-scale designs reflecting the current state and future potential of prefabricated architecture to be evaluated for exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art. Our scheme, one of five selected for construction on a site adjacent to the museum, was a five-story house with two bedrooms, two bathrooms, living and dining space, a roof terrace, and a carport. Its name was chosen to evoke a familiar material in capturing the concept of a sheer plastic, thinly wrapped residence.

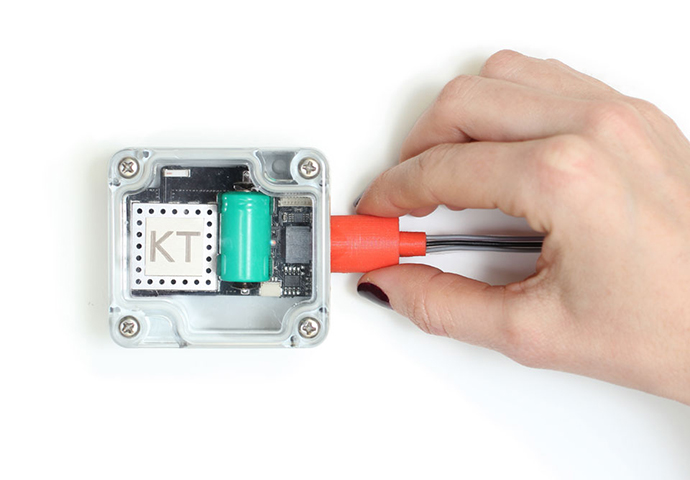

We had recently completed Loblolly House, an off-site fabricated home on the Chesapeake Bay, and were seeking to advance our development of SmartWrap™, a lightweight, energy-gathering building envelope composed of a multi-layer skin just a few millimeters thick. Cellophane House™ refines these methodologies and demonstrates a new future that may change the way the industry models, constructs, and delivers housing.

Assembly

Cellophane House™ was assembled like a car: The whole construction was broken down into integrated assemblies, called “chunks,” that were fabricated off site, then delivered via trailers to the site and stacked on top of each other with a crane. Eighty percent of the construction was completed in six days.

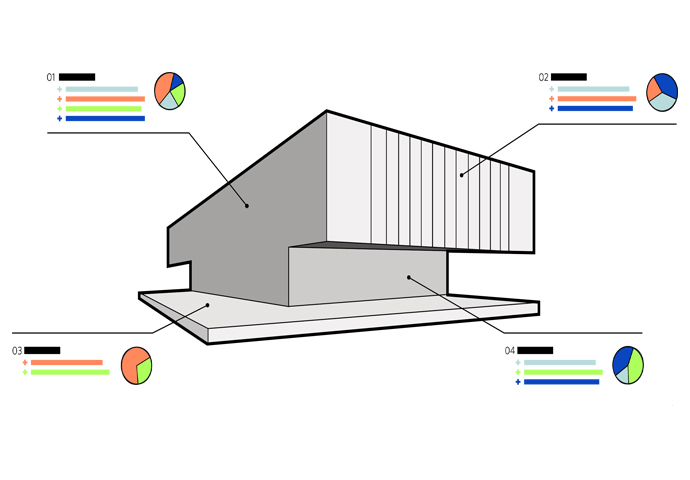

Materials were selected to be lightweight, minimizing embodied energy, and reusable within existing recycling streams. The same aluminum frame used for Loblolly House was scaled up from two stories to five, enabled by a strengthening system of custom-designed steel connectors. The SmartWrap™ skin was attached to that frame, with interior floors, ceilings, and partitions made of structural plastic. The skin was envisioned as a filter, selectively letting in daylight and seasonal heat and keeping out UV light and hot or cold air, depending on the season.

The super structure was completed in six days. This image shows a fourth floor chunk being lifted by crane.

© Albert Vecerka/Esto

Many prefabricated designs succeed in breaking down a building into modules that can be quickly joined together, but they typically embody a top-down strategy: design a building, and then devise a system to make it work. Here, we began with the frame-plus-components system as a basis, allowing architecture to grow out of its opportunities and constraints. Unlike prefabricated housing in which originality and site-specificity may be lost in the manufacturing process, Cellophane House™ is a flexible system of building that enables multiple outcomes. The frame can accommodate a variety of materials to suit different needs, tastes, and budgets; the house can adapt to different sites and climatic factors, and interior floor plans can be easily rearranged.

Disassembly

The final experiment at MoMA was its disassembly. The house was deglazed, un-stacked, and disassembled at ground level using basic handheld tools. Parts were organized on pallets and removed from the site in two days. Virtually no waste was generated, and 100 percent of the energy embodied in materials was recovered. The only remnant was a patch of gravel in an asphalt lot.